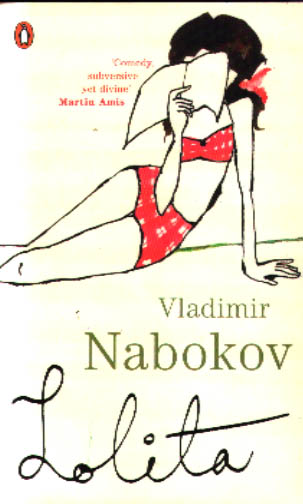

An article I submitted this month to Live Encounters, on Maurice Girodias, the “Lenin of the sexual revolution” – a Paris based publisher who dared to first publish many of the mid-late 20th century classics.

Category Archives: Writing

What Kind of Beast is This?

One of the questions most frequently asked in creative writing classes is “how long is a novel/play/short story/screenplay?” And, as is often the case in creative writing, the answer is that there are no rules but… there kind of are.

There is not an official cut off word count for any of the above literary forms but the publishing industry has generally accepted average lengths. Be alive to the fact that just because your word count has hit the “magic number”, it does not follow that you are finished. Apart from the fact you’ll be lobbing off at least a third in edits, you also need be sure that you have brought all the strands of your story to satisfactory conclusion, have made your point and your character has undergone some sort of change / journey / learning arc in the process. Otherwise, to paraphrase Truman Capote, your’re just typing.

What follows is a rough guide/ballpark figure for each literary form:

Novel

The average commercial novel is 78,000 words in length; this roughly amounts to 300 A4 pages in double spaced twelve-point font. However, a novel can be anything from 45,000 words onwards. A book between 20,000 – 45,000 is usually marketed as a “novella”.

Short Story

Traditionally, a short story is meant to be read in one sitting. Normally, this narrative form is quite pointed in its message, involves a single setting and few characters. A short story can be anything from 1,000-20,000 words.Writing short stories is a good way of building up your story telling skills, honing your craft as a writer and amassing a writing portfolio. Also, the short story is the literary form favoured by writing competitions. Such competitions usually look for stories in the 2,000-5,000 word bracket.

Flash Fiction

This is the short story’s kid brother. Somewhat akin to the Haiku, a flash fiction story often aims to capture a fleeting moment. It can be any thing between 100-1,000 words. Flash fiction is becoming very popular in competitions these days. Personally, I think this may be to save reading time for judges.

Screenplay

The standard “Hollywood” screenplay is 90 minutes long. Given the rule of thumb that one page equals one minute of movie, you should be aiming for a90-page long screen play. Obviously, this is an approximation.

TV/Play

Likewise, the page per minute rule applies here too. Bear in mind the slot your are aiming for. commercial TV and radio stations will include advert breaks in their schedule – so a half hour comedy show might in fact be only 22 minutes long etc… If you have a slot in mind, time the duration of the actual show (excluding theme music and commercial breaks.)

Stageplay

The page per minute rule can roughly be applied to stage plays too. If a stage play were to last an hour and a half, it should be 20,000 words long and span 90 pages.

Poem

A poem can be as short or as long as you like. A haiku is traditionally 17 syllables over three line. The Iliad is 25,000 lines long. For the try outs, however, you might aim for two or three verses.

grama rulz OK, innit!

Warning: You enter this grammar post at your own risk.

Once you’ve had your feedback and have chopped, pruned, rewritten and reshaped your work, you’re ready to go, right? Wrong. Next, you need to don your pernickety gloves and work on grammar, spelling and punctuation.

This type of revision is called a proofread and it is separate from the critique your friends gave re characters, story, POV, tone and structure. A proofread regards layout and correct use of language. A proofread is the final polish.

Never hand in a submission blighted by incorrect or inconsistent punctuation, bad grammar and misspelled words – thinking the story will shine through. They (the slush pile readers) will be turned off by your sloppy copy and will probably never read on into your story, so it won’t get that chance to shine through. If you’ve spent a year writing a novel, respect your work enough to spend another couple of weeks proofreading. It’s only common sense.

As you’ve probably read your own work countless times, you may be blind to copy mistakes. A keen eyed friend is invaluable here. Also you could cut a sentence sized gap in a blank page and place it over your text to check every sentence individually, with the rest of the text blanked out. This may sound painstaking but it is a very good focusing tool.

Many emerging writers are concerned about grammar, unsure of their own knowledge and application. I’ve been an English (as a foreign language) teacher for fifteen years and can recommend the following grammar self-study book (known in the TEFL world as ‘the grammar bible’): Raymond Murphy Grammar in Use. You’ll be able to pick up a cheap copy on Amazon. Spend a night or two doing the exercises, it’ll stand to you.

Also, I could wax lyrical about whether to use double or single quotes for dialogue (or to use any at all) and the difference between US and UK conventions regarding the same. However, I think the best is for you to take ten novels down from your shelf and see how the majority of them format dialogue and then apply the same convention to your work. Whichever you choose, ensure it is then consistent throughout your text.

Finally, here are some of the most common problems:

****Are you using the right “Its”?

“It’s” (with an apostrophe) is short for “it is”.

“Its” (no apostrophe) is possessive (ie: the dog lost its bone).

NOTE: somewhat confusingly, when you want to use the possessive elsewhere, you do use an apostrophe: “Mary’s coat”, “John’s golf club”, “the dog’s bone.”

****Same sound, different spelling (homophones).

“They’re”, “Their” and “There”.

They’re (they are) sitting the car. They’re listening to their (possessive) music, they’ll be fine there (preposition of place) for a while yet.

****Using “done” instead of “did” and vice versa.

“Done” is the past participle of “do” and is normally used with the auxiliary verb “have”. “Did” is the past simple of “do”.

(And if you have no idea what any of that means, you really do need to order that book).

So, you say either “I have done my homework” or “I did my homework” – and never “I done my homework,” or “he done his homework.”

****Saying “could of” rather than “could have” when using the second conditional tense or “could” as a modal verb in the perfect tense (yeah, see that grammar book).

“He could of gone to the shop,” is wrong.

“He could have gone to the shop,” is correct.

And please accept sincerest apologies for sending any of you off into a coma of boredom with this grammary post – believe me, it hurt me more than it hurt you.

RIP George Whitman

I’ve just read that George Whitman, the Paris-based American owner of Shakespeare and Co, has died aged 98.

I met George when I was 18 and a recently arrived backpacker in the city in the late 80s. It was 10:30am, he gave me a glass of whiskey and told me about knowing Henry Miller back in the day, and Samuel Beckett – who was still alive. It was my first taste of the expat bohemian life – and I shall always be in his debt for this introduction.

The shop has been run by his daughter, Sylvia, for some years and still reflects George’s generous and bohemian spirit. If you are in Paris, be sure to call in.

Thanks for the moment, GW! Shine on above the Seine.

Shellakybooky First Past the Post!!!!

My Radio Play Wins First Prize

Yeeessss! My radio play, ‘Shellkybooky’ has won first prize in the Annual Sussex Playwright’s competition – a national comp run from Brighton. A nice cheque and presentation of play is on the way… : ) Whatever else, 2011 has been a bumper year for my writing! BTW ‘shellakybooky’ is a Waterford word for a snail… and the play centres round a Liverpudlian Irish family of expats in Budapest Hungary and their son’s secret life as a graffiti enthusiast…

Killing Your Darlings

The Importance of Editing

‘Murder’ or ‘Kill your darlings’ is an adage attibuted to the literary critic Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, advising writers to cut the words / phrases to which they are most attached, in order to strenghten the work. It is good advice when editing, as often we writers shoehorn in a delicious description which doesn’t do an enromous amount for the piece as a whole. It is simply a bauble. Time to get the gun out.

Editing makes the job of writer a rather schizophrenic affair where one has to don two very different caps. The first cap is that of the creative free thinker who is focused on the big picture and is not too worried about the details. This is the person who comes up with the story, the theme, the basic structure, the person who invents characters and decides on the tone. This artist-writer will draw up the first draft of the story, writing only to please themselves. Finishing a draft wearing this cap is only some of the journey, however…

Next comes the cap of editor-writer. This is when the writer combs through the text, ruthlessly chopping, restructuring and cutting unnecessary/ unsuitable words, characters, scenes, phrases etc… or ‘murdering your darlings’. This is the writer preparing the text for other people. It is a good idea to leave a few weeks between your artist and editor incarnations.

Editing can be painful, and time-consuming. You’ve quite likely become attached to some characters, scenes, words and phrases and are loathe to see them go. Don’t worry, you can store them in your “writer’s bag” for use at a future time in a more suitable context. In the meantime, get pruning…

Chopping advice:

Cut all surplus adjectives and adverbs.

Examine the phrases you’ve shoehorned in just because you liked the sound of them – do they really fit that scene? Be honest. If not, bin them.

Take out all vague words such as “seem/seemingly” and try to do without your “justs”.

Look at all sentences that run for two or three lines. Do they really need to be that long? Can you reduce them or break them up? If you can, do so.

Active forms are better than passive forms, where possible (ie. “John cleaned the flat” rather than, “the flat was cleaned by John”).

Finally, every writer on Earth needs a reader or two – fresh eyeballs to run over your work and give you honest feedback. I suggest using three friends whom you trust will be frank with you. You don’t have to take everything they say on board. Do consider what they say, however, and if all three come back and say a character is not working. The character is not working. Rewrite.

Launch of Online Writing Course

Ladies and Gentlemen, introducing…. ‘Creative Writing: A Toolbox’

ClapClapClapClapClapClapClapClap

Ahem….

In response to all your lovely enquiries and requests, I’ve launched an online version of my workshop!

The six week online course, provides one-on-one coaching in the craft of creative writing, focuses on the basic tools, tricks and know how of the professional writer. Throughout this time, I provide constant feedback for your work and guidance in relation to editing, submission and markets.

‘Creative Writing: A Toolbox’ is supported by written material, exercise, assignments and a weekly 45 minute one-on-one online tutorial.

For more details please visit the ‘Services’ tab or contact: bpapartment at gmail dot com

The Show Me State

Telling: “Close the door,” she said nervously.

Showing: Her cigarette trembled in her hand: “Close the door.”

Telling: Peter was a fussy, neat sort of man.

Showing: Every Monday, Peter ironed and folded his towels into perfect squares and stacked them in the airing press, according to size and colour.

“Showing” your reader what your protagonist is thinking/doing, encourages your reader to engage more with your book/story/play, to interpret and picture what is going on. Showing also allows for more atmosphere and lends insight into character. Conversely, “telling” tends to deliver all the information neatly wrapped and can deny the reader all the fun of involvement and imagining.

Therefore, rather than telling the reader, ‘Bob was depressed,’ you might describe what Bob was doing and saying and the reader will also get a greater sense of ‘Bob’ if you do so.

Having said that, if the writer “shows” every inch of their novel it may bore the reader and slow the pace. There are times, for the sake of speed and economy, the writer needs to “tell”, so they can quickly move on to the next stage of the story.

If I could suggest a rule of thumb, it would be “show” the most important parts/events of the story and “tell” the minor linking passages. It’s your judgement call as to when and where to show or tell, but do give it thought.

Finally, please bear in mind the general consensus is that you always avoid telling via adverbs in speech attribution: “he said arrogantly”, “she shouted defiantly”, “we mumbled apologetically”. Instead, try to think of ways you could show this arrogance, defiance or apology.

The Third Man

The third person (he/she/it) is the most common narrative point-of-view. The third person observes the main character(s) from a distance, describing how others might see/consider your protagonist. In other words, it gives the narrator greater scope and view privileges than the first person narrator.

If you are writing an extended piece of fiction, you might find it easier and more accommodating to work with a third person narrator. The following are some varieties of this narrative point-of-view

* Nowadays, it is common to have a third person narrator that observes your main character whilst simultaneously looking over his/her shoulder and seeing the story almost from his/her point of view. This ‘over-the-shoulder’ third person narrator can provide some of the advantages of the first person without the drawbacks – however, it is somewhat limited as you are largely viewing events from your character’s POV. For emerging writers, this third person narrative may be a safer bet if wanting to attract an agent.

* You may want your narrator to be quite separate from your character, however. In which case, you could have your narrator follow him/her from a distance, observing actions as if a camera and not directly informing the reader of the character’s inner thoughts.

* Or you could have an omniscient third person narrator – a ‘God-like’ storyteller who sees all and knows all.

The “It” narrative

This is an unusual form of third person narration that tells a tale from the point of view of an object or an animal. An “it” narrative might conceivably be the story of a ring, told by the ring, as it recounts its many owners etc…

Multi narrators

Some books/plays/films are narratives told from various POVs. More common in Victorian prose than in contemporary writing, multi narrators allow for a vigorous description of a community and is useful if the author wants to concentrate on the interconnectivity of a place.

Whichever variety you choose, it is important to be style consistent throughout your work (or if you aren’t, have a reason for that).